Officially titled “Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Illegal and Irregular Allocation of Public Land”, the report was released in 2004 and remains one of the most significant documents in Kenya’s post-independence history. Chaired by Paul Ndung’u, the commission was established by the Kibaki administration to investigate how public land had been illegally or irregularly allocated between 1963 and 2002.

Key Findings

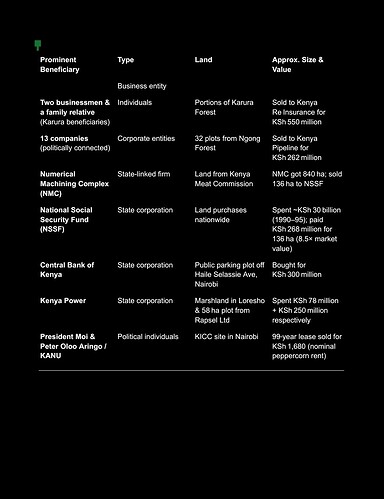

The report uncovered a pattern of systemic land grabbing, with over 200,000 illegal allocations affecting forests, school playgrounds, road reserves, wetlands, and land meant for public utilities. It exposed how public land became a currency for political patronage, especially under the Moi regime. Individuals close to the political elite—including ministers, senior civil servants, and well-connected businessmen—were granted public land at little or no cost, often through falsified records, backdated documents, and forged signatures.

Government institutions such as the Ministry of Lands, Commissioner of Lands, and provincial administrations were directly implicated in facilitating the land theft. These irregular allocations often displaced local communities, undermined environmental conservation, and weakened public trust in land administration.

Controversial Issues

-

Political Patronage: Land was distributed to reward loyalty and punish dissent. Some beneficiaries were given thousands of acres, sometimes overlapping with forest reserves or ancestral community lands.

-

Lack of Accountability: Although the report named powerful beneficiaries, few were prosecuted or forced to surrender their illegally acquired land.

-

Environmental Damage: Destruction of water catchment areas and public green spaces for private gain led to long-term ecological harm.

-

Colonial Legacy Overlooked: While addressing post-independence land theft, the report was criticized for not tackling historical colonial-era land dispossession—especially in the Coast, Rift Valley, and Central regions.

Supporters

Civil society groups, like the Kenya Land Alliance, human rights activists, and legal reformers, strongly supported the report. They demanded full implementation of its recommendations, including restitution, prosecution, and institutional reform.

Reformists in the Kibaki administration initially backed the report as part of a broader anti-corruption agenda, though support waned over time.

Opponents

Moi-era political elites, including former ministers and politically connected individuals, fiercely opposed the report. Some dismissed it as politically motivated and sought to block its implementation.

Parliament, in general, remained reluctant to act on the report, reflecting the wide-reaching implications it had on many sitting members.

Legacy

Despite its detailed documentation and bold recommendations, the Ndung’u Report has never been fully implemented. Its findings, however, continue to shape discussions around land reform, corruption, and transitional justice in Kenya. It remains a powerful reminder of how public resources were privatized for political gain—and how entrenched interests continue to block meaningful land reform.

TL:DR; Siasa mbaya, maisha mbaiya

CC:

@Landlord

@Gaines

@Straw_man

Any other tugege novice that thinks politics is simply about money.