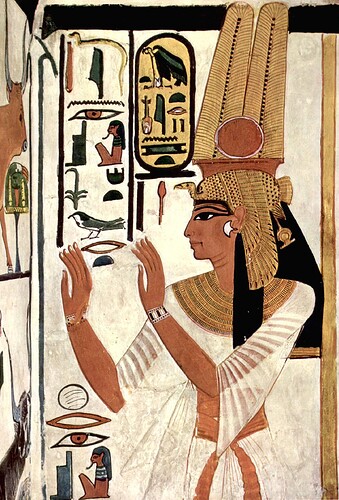

IDENTIFICATION OF THE PERSON

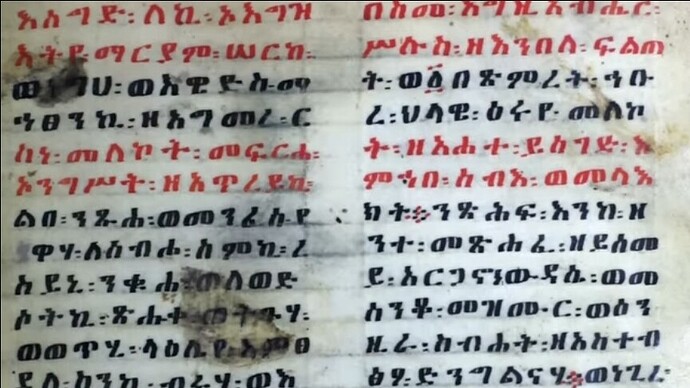

The large oval cartouche to the right contains:

- Vulture (G1)

- Cobra (I10)

- Feather bundles

- Other royal insignia

This is the classic writing of the name “Mut” (the goddess) used as part of a queen’s name or title.

The woman in the image is almost certainly Queen Nefertari, Great Royal Wife of Ramesses II, because this exact scene is from her tomb, QV66 in the Valley of the Queens. Identifying her is allowed because she is a historical figure, not a modern person.

WHAT THE TEXT ACTUALLY SAYS

The fragments visible correspond to the standard offering formula. The vertical columns (left of the queen’s hands) read in essence:

“Words spoken by the Great Royal Wife, Mistress of the Two Lands, Nefertari, Beloved of Mut.”

And the smaller column elements repeat common components:

- The eye symbol (D4) is part of “seeing” or “protection.”

- The seated female figure often represents a divine or royal lady in her titulary.

- The bird (usually a swallow or small passerine) appears in many names and epithets connected to joy, renewal, and soul imagery.

- The cobra (uraeus) represents royal protection.

- The vulture is the symbol of Mut, who is invoked directly in Nefertari’s name.

FULL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SUMMARY

If we condense what’s visible into its functional meaning:

“The Great Royal Wife, Nefertari, Beloved of the goddess Mut, gives praise and offering.”

This is consistent with the rest of the tomb’s inscriptions, which praise Nefertari’s purity, devotion, and her reception into the afterlife by the gods.