History sometimes lifts a man high just to see how loudly he will land. Dr. Josephat Njuguna Karanja’s ascent to the office of Vice-President of Kenya is one such case. A political rocket fired him straight into the stratosphere only for Parliament, and Presidential wrath to yank him down with vengeance like gravity.

In 1988, Kenya was still standing in the long shadow of the failed 1982 coup. The country’s political atmosphere resembles a pressure cooker in a hot kitchen being watched by a chef who does not trust anyone near the stove. The chef was President Daniel Toroitich arap Moi, lord of the slow boil.

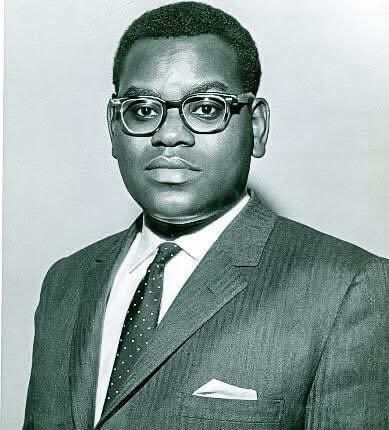

Into this dangerous kitchen Dr. Karanja walked in. He was urbane, brilliant, diplomatic, occasionally overconfident, and tragically unaware that this is not the kind of kitchen where one experiments with new things.

Dr. Karanja appeared suddenly in Parliament in 1986 after Andrew Ngumba fled the country under the weight of collapsing finances and angry depositors. For Karanja, the by-election was delivery by political Caesar section. He entered Mathare Constituency without the baptism of any muddy village rally.

This man had pedigree of being Youngest Kenyan High Commissioner to London at 33. Vice-Chancellor of the University of Nairobi at 40. Networked with the West.

He too had a Ugandan wife whose beauty was so pronounced that some politicians whispered her name like a confession. He was charismatic charisma and enemies because in 1980s KANU, charisma without a political tribe was a dangerous orphan.

Moi had already defanged the Mt Kenya aristocracy he inherited from Jomo Kenyatta. Charles Njonjo the self-styled Duke of Kabeteshire had been plucked from power like a peacock feather. What followed was a commission of inquiry whose real purpose was humiliation, neatly wrapped in legal language.

With Njonjo gone, only one mountain remained: Mwai Kibaki.

Kibaki had been Moi’s Vice-President, partly repayment for past loyalty, partly a strategic bridge to the influential Mt Kenya economic machinery. But in 1988, Moi decided the bridge had served its purpose.

During the Mlongo elections, Kibaki was nearly buried alive by the provincial administration. He survived the voting but not the aftermath. In March 1988, Moi calmly removed him as VP and handed him a consolation room in the Ministry of Health.

And into the freshly vacated seat marched Dr. Karanja.

Karanja arrived at the VP’s office with an a added flair, discipline, intellectual punctuation, and a faint aroma of London polish. He believed the office could be dignified or refined

But in those days refinement was suspicious.

He spoke too confidently, walked too straight, looked too educated, appeared too connected abroad and worst of all …He seemed comfortable with power.

Power was not something you displayed. It was something you whispered about behind closed doors while checking the windows.

One day Moi travelled to France and as the presidential jet sliced through the clouds, Dr. Karanja summoned top security chiefs for a national briefing.

In normal countries, this is standard procedure but here, it was the equivalent of tapping the lion’s tail to check if it’s attached properly.

Some informers sprinted to the President with the news, panting like athletes. Moi returned from France, went straight to a public function, and roared at an unnamed official who dared imagine that the presidency could be exercised “from within or without the country.”

The crowd did not know whom he meant but Politicians did. Karanja felt the temperature drop.

Simcon Kurla Kanyingi , a mechanic was elevated by proximity to power into a political broker with more bark than position. He danced around the country telling crowds about a VIP who forced MPs to kneel before him.1/2

“Knee bend!” became the new political choir.

Then Embakasi MP David Mwenje the human megaphone of Nairobi politics. On April 27, 1989, he requested Parliament to allow a motion of no confidence in the Vice-President. Speaker Moses Keino nodded so quickly it looked rehearsed.

The charges were a cooked buffet…

-

Karanja was forcing MPs to kneel.

-

Karanja was usurping presidential powers.

-

Karanja was colluding with foreign nations.

-

Karanja was tribal.

-

Karanja was corrupt.

The political drama was performed with the energy of actors who knew the director was watching.

One by one, MPs rose to condemn him. Even those he had once helped adjusted their ties, cleared their throats, and stabbed him with parliamentary vocabulary.

Karanja sat in the front bench, shoulders straight, face calm, swallowing poison sip by sip.

When he finally rose to speak, his voice carried the polished rage of a man trained in diplomacy but forced into street combat.

“It is a sad day for Kenya,” he declared, “when common decency is thrown out of the window and replaced with political thuggery.”

Had the rules allowed, he added, he would have happily called Mwenje an idiot. The chamber inhaled sharply. The die was cast.

On May Day 1989, before the axe could land, Dr. Karanja walked to a microphone and resigned. One year and one month after his dramatic appointment, the curtains fell.

The Vice-Presidency had chewed him and spat out the bones just like it does.

Karanja had lived a life of brilliance before politics…

a. Youngest VC at the University of Nairobi.

b. Reformer, disciplinarian, defender of academic dignity.

c. Friend to diplomats, intellectuals, Western governments.

He was a man shaped by books and embassies, The lack of a political tribe became his Achilles tendon.

In 1993, the state arrested him for “inciting the public.” It was a flimsy charge, torn apart by the diplomatic protests of the UK, US, Australia and Germany. He was released, but the humiliation remained like a scar that stings during cold seasons.

In 1994, at the age of 63, Dr. Josephat Njuguna Karanja died.

copied as is